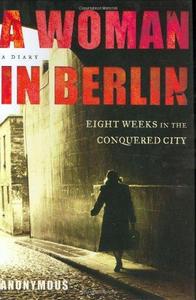

A Woman in Berlin

April-May, 1945 Berlin-A Perilous Place For A Woman!, April 22, 2009 By Bernie Weisz "a historian specializing in the Vietnam War (Pembroke Pines,Florida) E mail:BernWei1@aol.com Written originally for Amazon.com April 22, 2009 This review is from: A Woman in Berlin: Eight Weeks in the Conquered City: A Diary (Paperback) The Diary "A Woman In Berlin 8 weeks In The Conquered City" was written by an anonymous author for obvious reasons. I like to use actual quotes that the author used to explain the meaning of this book, as this truly conveys without any "subjective idiosyncratic coloring" what the writer is actually trying to say. Basically, this anonymous author, kept a written diary for 8 weeks in 1945, as Berlin, Germany fell to the approaching Communist Russian Army from the East. The first entry was recorded on Friday, April 20th, 1945 and the final one came on Thursday, June 14th, 1945. Quite a bit of history occurred during these 8 weeks, of which the most significant was the suicide of Adolf Hitler on April 30th, 1945 and the subsequent unconditional surrender of Germany to both the Allies and the Soviets. This woman was alone in Berlin at the time and kept a daily record of her and her neighbor's experiences in an attempt to both keep her sanity and record the plight of millions of Germans who expected the wrath and revenge of the oncoming Soviets. With what I called "gallows humor", the anonymous author describes in detail her conditions in a ravaged apartment building and how it's little group of residents struggled to get by amongst falling Soviet shells, death and rubble, with severe conditions such as no food, heat and water. The author also describes vividly how her fellow apartment dwellers displayed character traits ranging from chivalry and protectionism to cravenness and corruption, depraved first by hunger and then by the Russians. The reader will in shocking and vivid detail find out about the shameful indignities to which women in a conquered city were unequivocally subjected to, i.e. the mass rape suffered by all, regardless of age, social class or infirmity. To give the author credit, she did maintain throughout this book her resilience, decency, and fierce will to come through Berlin's trial until normalcy and safety returned somewhat. This book was first published 8 years after Germany's surrender (1953), but with public sentiment to put the specter of the war behind the public's view, it quickly disappeared from libraries and bookstores, lingering in obscurity for decades before it slowly reemerged. After it's reissuance, it became an international phenomenon over half a century after it was written. The book's forward describes the amazing way this diary was written: "The author, a woman in Berlin, took meticulous note of everything that happened to her as well as her neighbors from late April to mid-June 1945-a time when Germany was defeated, Hitler committed suicide, and Berlin was occupied by the Red Army. While we cannot know whether the author kept the diary with eventual publication in mind, it's clear that the "private scribblings" she jotted down in 3 notebooks (and a few hastily added slips of paper) served primarily to help her maintain a remnant of sanity in a world of havoc and moral breakdown. Crimes of War 2.0: What the Public Should Know (Revised and Expanded) The earliest entries were literally notes from the underground, recorded in a basement where the author sought shelter from air raids, artillery fire, looters, and ultimately rape by the victorious Russians. With nothing but a pencil stub, writing by candlelight since Berlin had no electricity, she recorded her observations, which were at first severely limited by her confinement in the basement and dearth of information. In the absence of newspapers, radio, and telephones, rumor was the sole source of news about the outside world. As a semblence of normalicy returned to the city, the author expanded her view, and began reporting on the life of her building, then of her street, then on the forced labor she had to perform and her encounters in other neighborhoods. Beginning in July, 1945, when a more permanent order was restored, she was able to copy the contents of her three notebooks on a typewriter". Ther result was this book I am reviewing. While it is obvious that the author was an experienced journalist prior to the war (her verbiage, syntax and ideation is not of an amateur), she mentions in the diary that before the war she had made several trips abroad as a reporter and had visited the Soviet Union, where she picked up a rudimentary knowledge of speaking Russian. This might have saved her life in dealing with the various Soviet soldiers she dealt with, was pillaged sexually by, and eventually turned the tables on by manipulating these Russians with "sex for food". Because of the multiple rapes, it is understood that this author choose to remain anonymous. However, the individual that translated this from German into English, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, wrote this interesting forward to his translation. Mr. Enzensberger wrote that the anonymous author: "met Kurt W. Marek, a journalist and critic who facilitated the publication of the diary. An editor at one of the first newspapers to appear in the new German state, he went to work for "Rowohlt", a major Hamburg publishing house. It was to Marek that the author entrusted her manuscript, agreeing to change the names of people in the book and eliminate certain revealing details. In 1954 Marek placed this version of the book with a publisher in the United States, where he had settled. Thus, "A Woman in Berlin" first appeared in English (in an earlier translation) and then in 7 other languages. It took more than 5 years for the German original to find a publisher and even then that company, "Helmut Kossodo" was not in Germany but in Switzerland. But German readers were obviously not ready to face some uncomfortable truths, and the book was met with either hostility or silence. One of the few critics who reviewed it complained about the author's "shameless immorality". German women were not supposed to talk about the reality of rape; and German men preferred not to be seen as impotent onlookers when the Russians claimed the spoils of war. Ivan's War: Life and Death in the Red Army, 1939-1945 According to the best estimates, more than 100,000 women were raped after the conquest of Berlin. The author's attitude was an aggravating factor:devoid of self-pity, with a clear-eyed view of her compatriot's behavior before and after the Nazi regime's collapse. Her book flew in the face of the reigning postwar compacency and amnesia. No wonder the diary was quickly relegated to obscurity. By the 1970's, the political climate had become more receptive, and photocopies of the text, which had long been out of print, began to circulate in Berlin among the radical students of 1968 and the burgeoning women's movement. By 1985, when I started my own publishing venture, I thought it was time to reprint "A Woman in Berlin", but the project turned out to be fraught with difficulty. The author could not be traced, the original publisher had disappeared, and it was not clear who held the copyright. Kurt Marek had died in 1971. On a hunch I contacted his widow, Hannelore, who knew the identity of the author. She also knew that the diarist did not wish to see her book reprinted while she was alive-an understandable reaction given the dismal way it was originally received. In 2001, Ms. Marek told me that the author had died and her book could now reappear. By then, Germany and Europe had undergone fundamental changes and all manner of repressed memories were reemerging. It was now possible to publish the diary in it's full, complete form for the first time and restore passages that had previously been excluded, either to avoid touching on delicate matters or to protect the privacy of people still alive". How do we know this diary is legitimate after the publishing of the fraudulent and fictitious "Last Letters from Stalingrad" was found to be fictitious 40 years after it's writing? And what about the scandal over the "fake Hitler diaries and the "David Irving Trial"? During the fall of Berlin in 1945, Anthony Beever, a preeminent historian, wrote his introduction in this book in regard to the authenticity of this diary. Mr. Beever wrote: "It is perhaps inevitable that in the absence of an author, some have raised doubts over the authenticity of the work, but experts on personal documents from the period have confirmed that the diary's transcript is original and completely genuine. Such questions are to be expected, however, particularly after the scandal over the fake Hitler diaries, and after the great bestseller of the 1950's "Last Letters From Stalingrad" was found to be fictitious more than forty years following it's initial appearance. On reading "A Woman in Berlin" for the first time in 1999, I instinctively compared my reactions to those I'd had to the Stalingrad letters, which had quite easily made me uneasy. They were too good to be true. Yet any suspicions I might have had about "A Woman in Berlin" were soon discarded. The truth lay in the mass of closely observed detail. The anonymous diarist possessed an eye so consistent and authentic that even the most imaginative forger would never have been able to reproduce her visions of events. Just as importantly, other written and oral accounts that I have accumulated during my own research into the events in Berlin attest to the truth of the world she describes". I can, by personal experience attest to this. My father was in Germany in June, 1945 in the British sector of Allied-controlled Berlin. His name was David Weisz. He had met Soviet troops roaming and plundering from the prostate German citizenry. My father keenly noticed that a Soviet soldier would steal before anything else a wristwatch off a person, dead or alive. He had seen Soviet soldiers with wristwatches, 5 or 6 at a time, on a Russian's arms and ankles. My father passed away in 1984, and, while bizarre, I had forgotten that story until I read a passage in "A Woman in Berlin". The anonymous author noted about the Russian conquerors: "They keep pulling out their watches, comparing the time, the Moscow time they brought with them, which is an hour ahead of ours. One of the men has a thick old turnup of a watch, an East Prussian brand, with a shiny yellow, highly concave dial. Why are they so fixated on watches? It's not because of the monetary value;they don't ogle rings and earrings and bracelets the same way at all. They'll overlook them if they can lay their hands on another watch. It's probably because in their country watches aren't available for just anyone and haven't been in a long time. You have to really be somebody before you can get a wristwatch, that is, before the state allots you something so coveted. And now, they're springing up like radishes ripe for the picking, in undrempt-of abundance. With every new watch, the owner feels an increase in power. With every watch he can present or give away back home, his status rises. That must be it. Because they can't distinguish between a cheap watch and an expensive one. They prefer the ones with bells and whistles-stopwatches or a revolving face beneath a metal case. A gaudy picture on the dial also attracts them". I am convinced that the only way this author would know what my father told me 25 years ago was because she was there! There are many pearls of history dropped in this book, such as the various situations in which the author and her fellow female associates were raped and the circumstances surrounding it. Furthermore, the reaction of the author and her contemporaries to the defeat of Nazism, the suicide of Ava Braun and Hitler, the institution of the Soviet economy and the way the Soviets in the initial months of occupation carted off all usable machinery and industrial capability back to the Soviet Union by railroad are all chronicled and discussed. There is one glaring defect that I noted the author left out. Of course, the vanquished Nazi leaders were punished at the Nuremburg Trials of 1947. What happened to all the perpetuators of the mass rapes? Obviously, it will never be possible to calculate the exact number of rape victims in 1945. Anthony Beever believes: "A general estimate given is 2 million German women; this figure excludes Polish women and even Soviet women and girls brought to Germany for slave labor by the Wehrmacht. But the figures for Berlin are probably the most reliable of all of Germany-between 95,000 and 130,000, according to two leading hospitals. In another study by the "Crimes of War Project", it is noted: " The history of the twentieth-century warfare has shown, though, how little formal and customary laws of war have been observed-and how rarely they have been enforced. The Soviet Army raped its way across Prussia and into Berlin in the final days of W.W. II, yet Moscow's military judges took a victor's place of honor on the bench at Nuremberg. In fact, the founding statute of the International Military Tribunal in Nuremburg made no specific reference to rape, relying on language prohibiting inhumane treatment to encompass rapes committed by Nazi's". Nuremburg Trials Transcripts Volume 5 - Trial of the War Criminals International TribunalThe author did not address culpability for the sexual violations of herself or others. However, Anthony Beever did. He offered this explanation. Beever reflected: "One of the most important aspects of this diary is it's careful and honest reflection on rape in war. The whole subject of mass rape in war is hugely controversial. Some social historians argue that rape is a strategy of war and that the act itself is one of violence, not sex. Neither of these theories is supported by events in Germany in 1945. There have indeed been cases of rape being used as a terror tactic in war-the Spanish civil War and Bosnia are two clear examples. But no documents from the Soviet archives indicates anything of the sort in 1945. Stalin was merely amused by the idea of Red Army soldiers having "some fun" after a hard war. Meanwhile, loyal Communists and commissars were taken aback and embarrassed by the mass rapes. One commissar wrote that the Soviet propaganda of hatred had clearly not worked as intended. It should have instilled in Soviet soldiers a sense of disgust at the idea of having sex with a German woman. The argument that rape has more to do with violence than sex is a victim's definition of the crime, not a full explanation of male motive. Certainly, the rapes committed in 1945-against old women, young women even barely pubescent girls-were acts of violence, an expression of revenge and hatred. But not all of the soldier's anger came in response to atrocities committed by the Wehrmacht and the SS in the Soviet union. Many soldiers had been so humiliated by their own officers and commissars during the four years of war that they felt driven to make amends for their bitterness, and German women presented the easiest target. Polish women and female slave laborers in Germany also suffered. More pertinent, Russian psychiatrists have written of the brutal "barracks eroticism" created by Stalinist sexual repression during the 1930's (which may also explain why Soviet soldiers seemed to need to get drunk before attacking their victims). Most important, by the time the Red Army reached Berlin, eyewitness accounts show that revenge and indiscriminate violence were no longer the primary factors. Red Army soldiers selected their victims more carefully, shining torches in the faces of women in the air-raid shelters and cellars to find the most attractive. A third stage then developed, which the diarist also describes, where German women developed informal agreements with a particular soldier or officer, who would protect them from other rapists and feed them in return for sexual compliance. A few of these relationships even developed into something deeper, much to the dismay of the Soviet authorities and the outrage of wives at home". Finally, while there was a smattering of resentment by the author toward the Nazi's for leaving Germany in total ruins, it was not at the level of anger I thought it would be. Regardless, this story was a priceless microcosm of the senseless fallout and destruction caused by the fury of the Second World War that inevitably touched the undeserved, the weak, the old and the unprotected. Rape can never be justified as a part of warfare regardless of the situation at large, and stricter laws and sanctions must be enacted to enforce this for the future. This book taught me events and occurrences of W.W. II that rarely are mentioned in any history book! Source: OpenLibrary

In your inventory

In your friends' and groups' inventories

Nearby

Elsewhere

Edition - isbn:9780805075403 - inv:e4e677670de032518079d1ca61918027